Navigating Family Law: The Path Through Divorce and Separation in Ontario

When marriages or common-law relationships end, families face a complex mix of legal and emotional challenges. Questions about parenting, finances, and property division demand careful attention. Understanding Ontario’s family law landscape helps you protect your rights, set realistic expectations, and navigate this transition more effectively. This guide explores the key issues you’ll encounter and the resources available to support you.

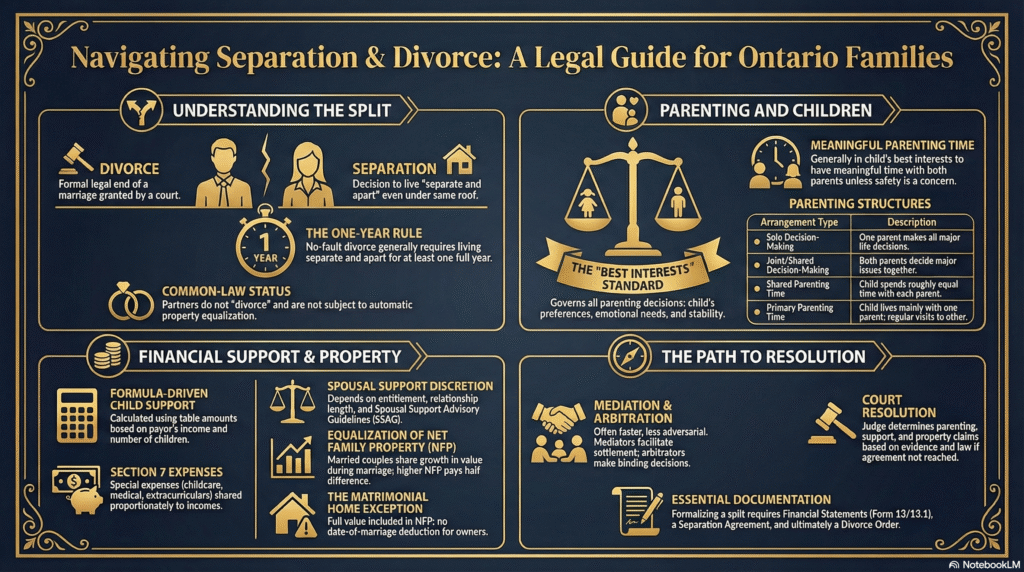

Understanding Divorce and Separation in Ontario

What’s the Difference?

The terms “divorce” and “separation” mean different things in Ontario law, and understanding the distinction is important.

A divorce is the formal legal end of a marriage, granted by a court under the federal Divorce Act. Once finalized, it allows you to remarry and provides closure to the marital relationship. To obtain a no-fault divorce, spouses must have lived separate and apart for at least one year—which can include living under the same roof if they maintain separate lives. You can also obtain a divorce on grounds of adultery or cruelty without waiting, though this is less common.

A separation occurs when married partners decide to live separate and apart, ending their cohabitation while remaining legally married until divorce is granted. Despite being separated, you still need to address legal matters like parenting, support, and property division. These issues are typically governed by Ontario’s Family Law Act and Children’s Law Reform Act.

Common-law partners follow a different path. Since they were never legally married, they don’t go through a divorce process. When their relationship ends, they address parenting, child support, and any property or support claims based on equitable principles like unjust enrichment or constructive trust, rather than the automatic equalization regime that applies to married couples.

Common Misconceptions

Several myths about divorce and separation can lead to poor decision-making. Separation does not legally bind you to marital obligations like fidelity—in fact, you and your spouse are free to form new relationships, though evidence of infidelity may remain relevant in limited legal contexts. A separation agreement alone doesn’t legally end a marriage; you need a divorce judgment for that. Many separations are also resolved amicably through negotiation and mediation rather than contested court battles. Finally, support and property rights often persist after separation unless clearly addressed by agreement or court order, and common-law partners cannot “divorce”—they simply separate and resolve their legal claims based on different principles.

Key Family Law Issues in Separation and Divorce

Parenting and Parenting Time

After separation or divorce, one of the most important issues is determining how parenting responsibilities and time will be shared. Ontario law focuses on the best interests of the child in all parenting decisions, as outlined in the Children’s Law Reform Act and Divorce Act.

The types of parenting arrangements include sole decision-making (one parent makes major decisions), joint or shared decision-making (both parents decide together), shared parenting time (roughly equal time with each parent), split arrangements (siblings live with different parents), and primary parenting time (children live mainly with one parent with regular time with the other).

How courts decide parenting arrangements involves examining several factors: the child’s best interests and expressed preferences (depending on age and maturity), the quality of each parent’s relationship with the child, each parent’s ability to meet the child’s physical, emotional, cultural, and educational needs, the history of parenting involvement, any mental health or substance-use issues, evidence of family violence or abuse, each parent’s ability to cooperate, work schedules and family support systems, and the value of stability and avoiding unnecessary disruption.

Parenting time for the less-involved parent is generally recognized as important for the child’s wellbeing. Courts typically find that it is in the child’s best interests to have meaningful parenting time with both parents, unless safety or other serious concerns make this inappropriate. This typically includes overnights, weekends, holidays, and school breaks, though arrangements may be supervised or restricted if safety concerns exist.

Modifying parenting arrangements is possible when circumstances change significantly. The parent seeking a change must demonstrate a genuine change in circumstances, that the new arrangement serves the child’s best interests, and that the benefits outweigh any disruption caused.

Child Support

Child support recognizes that both parents have a responsibility to financially support their children according to their needs and the family’s standard of living. Ontario uses the Federal Child Support Guidelines and Ontario’s Child Support Guidelines (O. Reg. 391/97), which establish “table amounts” based primarily on the paying parent’s annual income and the number of children.

How the Tables Work

Calculating the basic amount starts with guideline tables. A parent earning $60,000 annually, for example, would pay a set monthly amount for one child, more for two children, and so on. Courts also consider special or extraordinary expenses (called “section 7 expenses”)—childcare, uninsured medical and dental costs, certain educational expenses, and extracurricular activities—which are typically shared between parents in proportion to their incomes.

When Support Can Change

When table amounts may be adjusted, undue hardship cases allow courts to depart from the standard table amount if strict criteria are met. When a child spends at least 40% of time with each parent, set-off or shared-custody calculations may apply instead of the full table amount. Courts generally do not reduce child support based on the recipient parent’s income, though income matters for sharing section 7 expenses and for shared-custody analysis.

Duration and Modification

Duration of support typically continues until the child is no longer a “child of the marriage” or a dependent child under provincial law. This usually means until age 18 and the end of full-time school, though support may continue through full-time post-secondary education or if the child has an illness or disability requiring ongoing support.

Enforcing and modifying support can involve wage garnishment, bank seizures, and driver’s license suspension for non-payment through the Family Responsibility Office (FRO). If circumstances change significantly—such as job loss, income increases, or significant changes in a child’s needs—support can be modified. The paying parent must provide updated financial information for reassessment, and many agreements include automatic adjustments for inflation or income changes.

Spousal Support

Unlike child support, which is primarily formula-driven, spousal support depends on individual circumstances and is often subject to negotiation and discretion. Eligibility and calculation are governed by the Family Law Act and Divorce Act.

Who qualifies for spousal support depends on demonstrating both entitlement and the other spouse’s ability to pay. Courts consider the length of the relationship, each spouse’s roles (breadwinner, caregiver, homemaker), health and age, education and employment history, capacity for self-support, loss of marital standard of living, and economic disadvantages caused by the relationship. Support may be awarded on compensatory grounds (to address career sacrifices or disadvantages imposed by the relationship) or needs-based grounds (addressing economic hardship from the relationship’s breakdown).

Calculating support amounts relies heavily on the Spousal Support Advisory Guidelines (SSAG), which suggest ranges based on each spouse’s income, length of marriage, and whether dependent children are involved. While not legally binding, courts frequently follow the SSAG and explain any significant departures. The calculation also considers the recipient’s actual needs, the parties’ overall financial circumstances (including any equalization payment), and the goal of promoting self-sufficiency where reasonable.

Duration and modification may be time-limited (set to end on a specific date) or indefinite. Many agreements include provisions for periodic review or cost-of-living adjustments. Spousal support may end on the terms specified in the court order or agreement, and can be reviewed if there is a significant change in circumstances—such as significant income changes, retirement, or shifts in the recipient’s financial need or capacity for self-support. Remarriage or cohabitation by the recipient can be relevant to reassessing need, though it does not automatically terminate support in every case.

Property Division for Married Spouses

Ontario uses an equalization system for married spouses, quite different from how common-law partners’ property is treated. This system is governed by the Family Law Act and aims to fairly share the growth in property value during the marriage, rather than physically dividing every asset.

How equalization works involves calculating each spouse’s Net Family Property (NFP) as of the separation date. Each spouse’s assets minus debts are valued, certain date-of-marriage deductions are applied, and excluded property (such as gifts, inheritances kept separate, and some insurance proceeds) is removed from the calculation. The spouse with the higher NFP generally pays the other an equalization payment equal to half the difference between their NFPs.

What counts as family property includes most assets and debts accumulated during the marriage, subject to the specific calculation rules in the Family Law Act. Excluded property—which belongs to one spouse only—typically includes gifts and inheritances received during the marriage and kept separate, life-insurance proceeds, and certain personal-injury settlements.

Special assets requiring careful treatment include pensions (valued and divided under pension legislation and family law rules), businesses (requiring independent valuation), and the matrimonial home (which receives unique treatment). The matrimonial home is special because its full value on the separation date is included in the NFP calculation, and the spouse who owned it on the marriage date does not receive a date-of-marriage deduction for its value. This means the entire growth in the home’s value—and even its premarital value—is effectively shared between spouses through equalization.

For common-law partners, property is not divided under the Family Law Act’s equalization regime. Instead, they may pursue equitable claims such as unjust enrichment or constructive trust, which are more fact-specific and discretionary, requiring proof of contribution and enrichment.

Tax Implications

Understanding the tax consequences of support and property division can prevent unexpected liabilities.

Spousal support that is periodic, court-ordered, or paid under a written agreement meeting Income Tax Act requirements is taxable to the recipient and tax-deductible to the payor. Child support, by contrast, is neither tax-deductible for the payor nor taxable income for the recipient under current Canadian tax rules. Lump-sum payments and arrears may be treated differently for tax purposes, so obtaining tax advice during negotiation or variation of support is important.

Property transfers between spouses or former spouses often occur on a tax-deferred “rollover” basis under the Income Tax Act when made to settle marital property rights. However, selling or dividing certain assets—such as investment properties, registered accounts, or corporate interests—may trigger tax consequences. Consulting a qualified tax professional is recommended for complex or high-value asset divisions.

Resolving Separation and Divorce: Your Options

Starting the Process

In Ontario, either spouse can initiate the separation or divorce process by seeking legal advice from a family law professional. This helps clarify your rights and options under the Divorce Act and Family Law Act. Separation itself simply means one spouse decides the relationship is over and they begin living separate lives—even if still under the same roof, you’re separated if you intend to end the relationship and live separate and apart.

The Documents You’ll Need

To formalize the process, several documents are typically involved. An Application for Divorce or Application (Family Law) formally asks the court to grant a divorce and/or address parenting, support, and property matters. For a no-fault divorce, you must provide evidence of at least one year of separation. A Separation Agreement is a private contract recording agreed terms about parenting, support, and property without ending the marriage.

For full disclosure, you’ll complete Financial Statements (sworn forms like Form 13 or 13.1) detailing income, expenses, assets, and liabilities, giving each party a clear picture of the other’s financial situation. Ontario court forms are available through the Ontario Superior Court of Justice.

To finalize matters, a Separation Agreement or Minutes of Settlement records agreed terms and is legally enforceable. If court is involved, a Divorce Order or Judgment formally ends the marriage and incorporates or sets out parenting, support, and property terms. Because document requirements vary with circumstances and location, obtaining legal advice ensures all necessary steps are completed properly.

Alternative Dispute Resolution: Mediation and Arbitration

Not every separation requires a contested court process. Ontario recognizes two main alternatives to litigation.

Mediation involves a trained mediator helping spouses communicate, identify issues, and work toward mutually acceptable settlements regarding parenting, support, and property. The mediator doesn’t decide the outcome; the spouses do. This approach can save time and cost and is typically less adversarial than litigation while still producing enforceable agreements. Learn more from the Ontario Association for Family Mediation.

Arbitration is more formal. An arbitrator acts like a private judge, hearing evidence and submissions from both parties, then making a binding decision in accordance with the Arbitration Act, 1991 and the Family Law Act. Arbitration provides faster resolution than court in some cases and allows more privacy, though the decision is legally binding. For more information, visit the ADR Institute of Ontario.

Both methods can result in enforceable outcomes and may be combined—for example, spouses might mediate some issues and arbitrate others.

Court Resolution

If spouses cannot reach agreement through negotiation, mediation, or arbitration, a judge will determine parenting arrangements, child support, spousal support, and property claims based on evidence and applicable law. This process takes longer and costs more than settlement but provides a formal resolution when agreement is impossible.

Making It Final

Whether resolved by agreement or court decision, final terms are documented in a legally binding agreement or court order addressing all financial and legal obligations. Complying with these terms is essential—orders can be enforced through the courts and, for support, through the Family Responsibility Office.

The Emotional Journey: Supporting Yourself and Your Children

Divorce and separation bring intense emotions—grief, anger, fear, and uncertainty are normal. Recognizing these impacts and seeking support is crucial to moving through this transition.

For yourself, consider seeking counselling from a therapist experienced in separation and divorce to process emotions and develop coping strategies. Joining a support group connecting you with others facing similar challenges can provide validation and practical insights. Lean on trusted friends and family, and prioritize self-care through healthy routines, sleep, nutrition, and exercise. Healing takes time, and accessing both professional and personal support makes the process more manageable.

For your children, the transition often brings confusion, anxiety, or feelings of responsibility. Reassure them that the separation is not their fault and that both parents love them. Maintain consistent routines to provide security and structure. Encourage open communication and listen to their concerns without judgment. Watch for signs of distress such as changes in behaviour, school performance, or mood, and seek professional help if difficulties persist so they can process emotions safely. Every child reacts differently, so patience and stability are key to supporting them through family changes.

Taking the Next Steps

Ending a marital or common-law relationship combines legal complexity with emotional challenges. The major issues you’ll face include parenting decision-making and time schedules, child support amounts and special expenses, spousal support eligibility and duration, property division and equalization, and the tax and debt implications of your arrangements.

Informed decisions and trusted professional support are crucial. Consulting with an experienced family law lawyer protects your rights and interests regarding parenting, support, and property. Emotional support through counselling, peer groups, and personal networks helps you cope and rebuild. Out-of-court resolution methods like mediation and arbitration can facilitate more amicable settlements and help families move forward with greater stability.

While separation or divorce is difficult, it can also mark the beginning of a new chapter and personal growth. Taking a collaborative and respectful approach to resolving disputes—rather than adopting an adversarial stance—benefits you, your former partner, and most importantly, your children.

Additional Resources

The following resources provide information and support:

Government and Court Resources

- Ontario Superior Court of Justice – Court forms, procedures, and information

- Family Responsibility Office (FRO) – Child and spousal support enforcement

- Ministry of the Attorney General – Family Law Information – Government guidance and resources

- Justice.gc.ca – Family Law – Federal family law information

Legal Guidance and Professional Services

- Law Society of Ontario – Find a Lawyer – Locate certified family law specialists

- Legal Aid Ontario – Free or low-cost legal services for eligible individuals

Dispute Resolution Services

- Ontario Association for Family Mediation – Find accredited family mediators

- ADR Institute of Ontario – Arbitration and mediation professionals

Emotional Support and Counselling

- Ontario Psychotherapy Network – Find counsellors and therapists

- Distress Centers Ontario – Crisis support and referrals

- Canadian Mental Health Association – Mental health resources and support

Child Support Information

- Federal Child Support Guidelines – Official guideline tables and regulations

- Ontario Child Support Guidelines (O. Reg. 391/97) – Provincial regulations

Legislation and Guidelines

- Divorce Act – Federal divorce legislation

- Family Law Act – Ontario family law legislation

- Children’s Law Reform Act – Ontario children’s law legislation

- Spousal Support Advisory Guidelines (SSAG) – Federal advisory guidelines

- Income Tax Act – Tax implications of support and property

Legal Disclaimer: The information in this article is for general informational purposes only and is not legal advice.